[Article under construction]

Note that the PACT goalsetting framework was originally coined by Anne-Laure Le Cunff, see her article here.

Summary

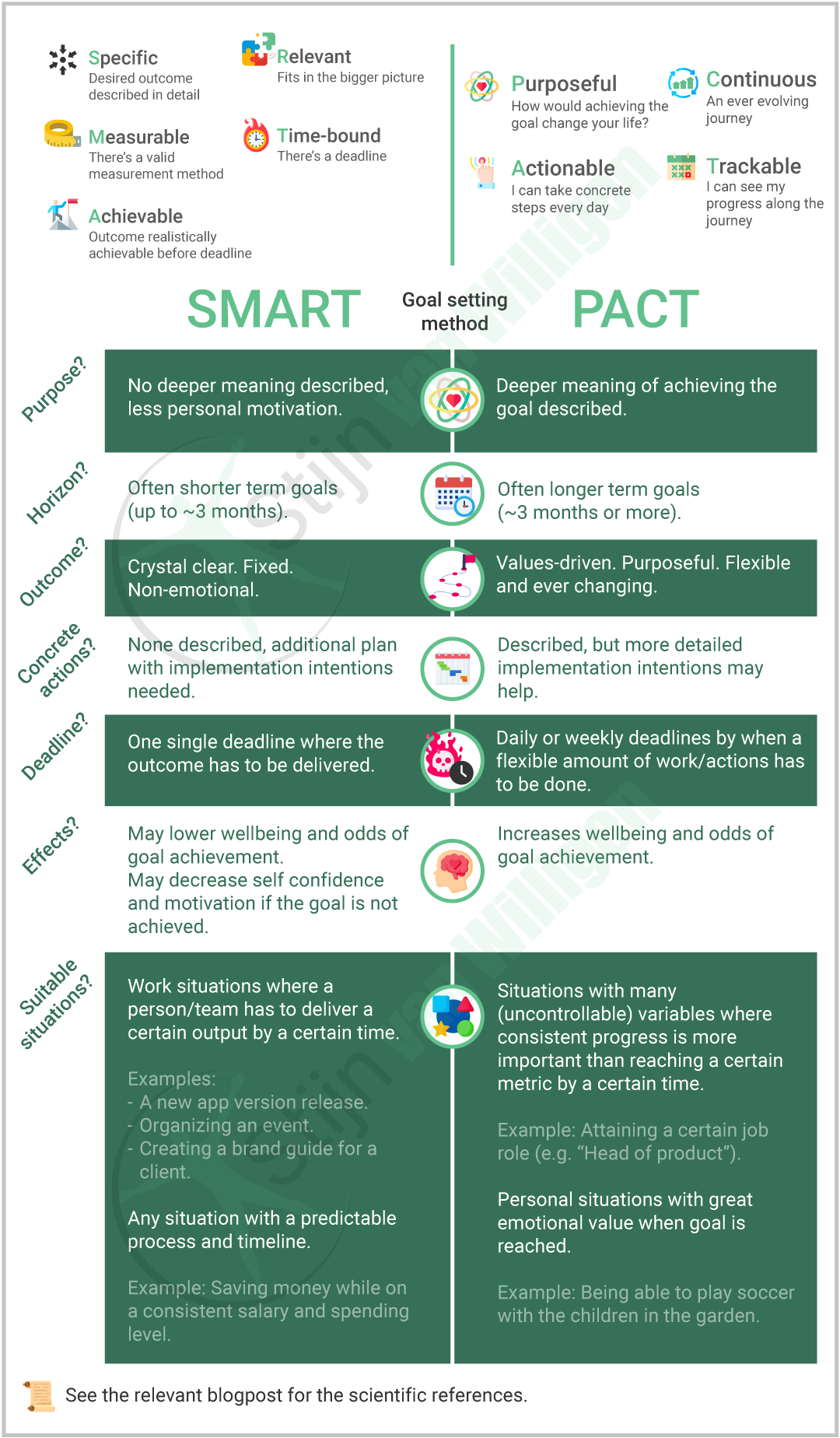

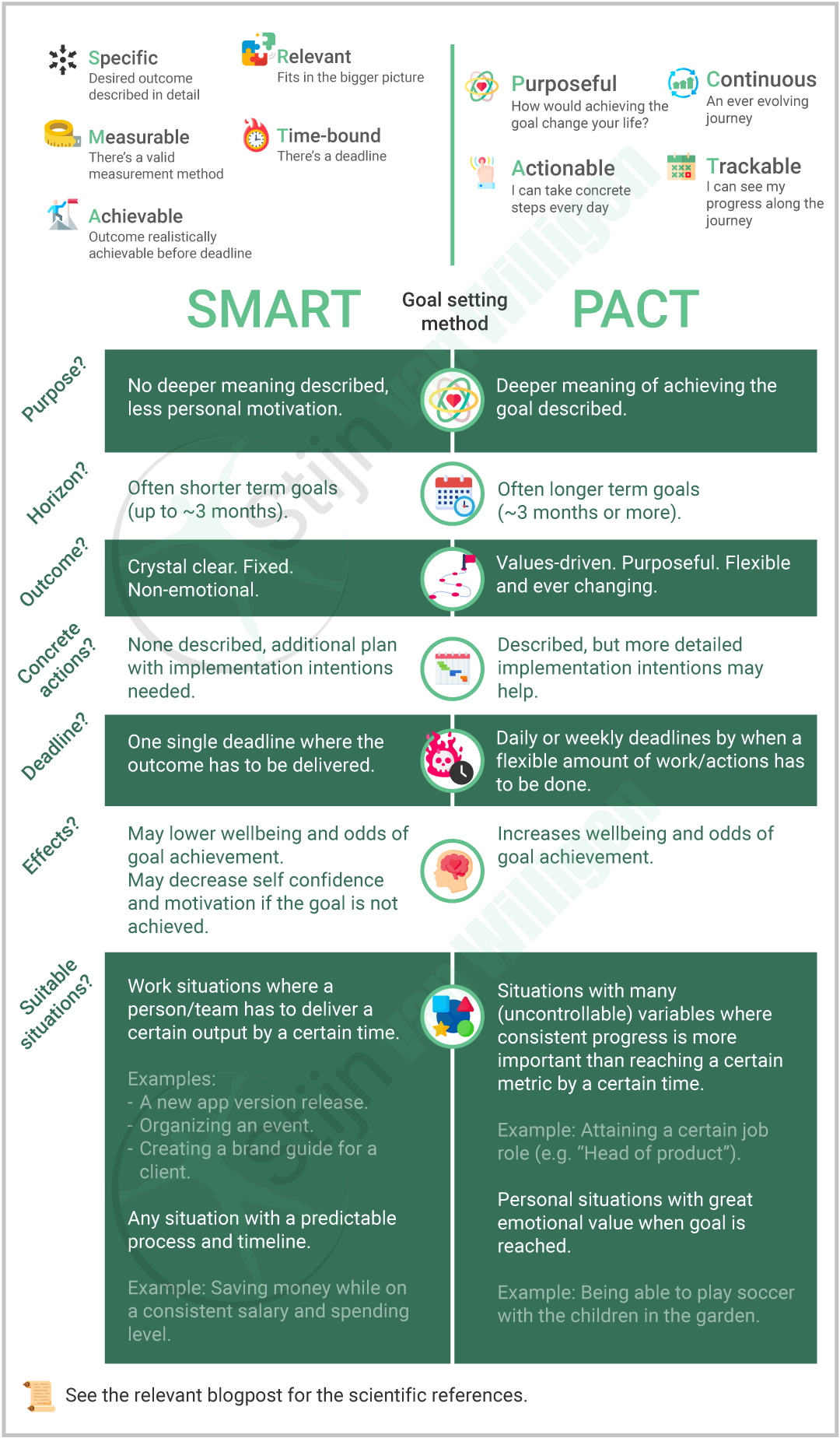

The image below visualizes the main differences between the two goal setting methods, and which method suits which situation: |

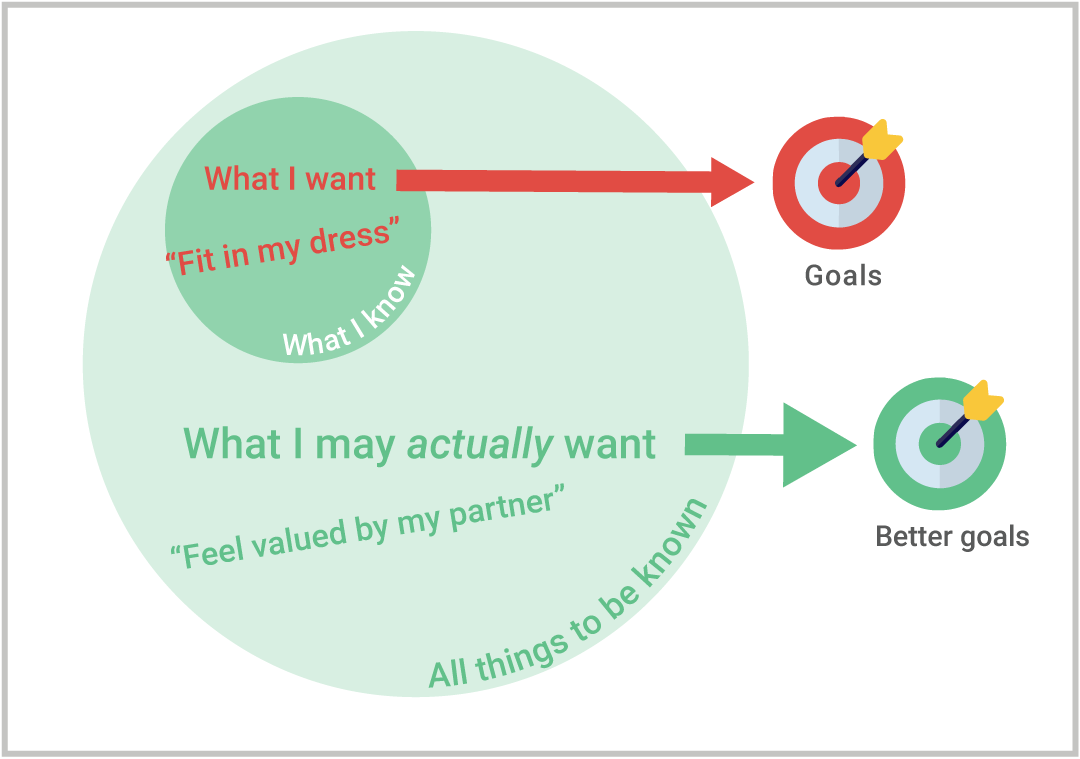

“Most people don’t know what they want, but want what they know.” – Chi Chiu

And even when you do know what you want (which a counseling session can greatly help with), have you previously tried formulating this “want” into a “SMART goal”?

But did it feel like something was missing in SMART goal-setting?

Or perhaps you later found out you misjudged how long it would actually take to reach the goal, causing a lot of last-minute stress to get the job done in time?

Maybe during the journey to reach your goal you realized you wanted to change the goal to something else?

Did not achieving a goal hurt your self-confidence? Discouraged from trying again?

You’re not alone. We have all experienced it.

Yet the above shouldn’t scare us away from setting goals in the first place.

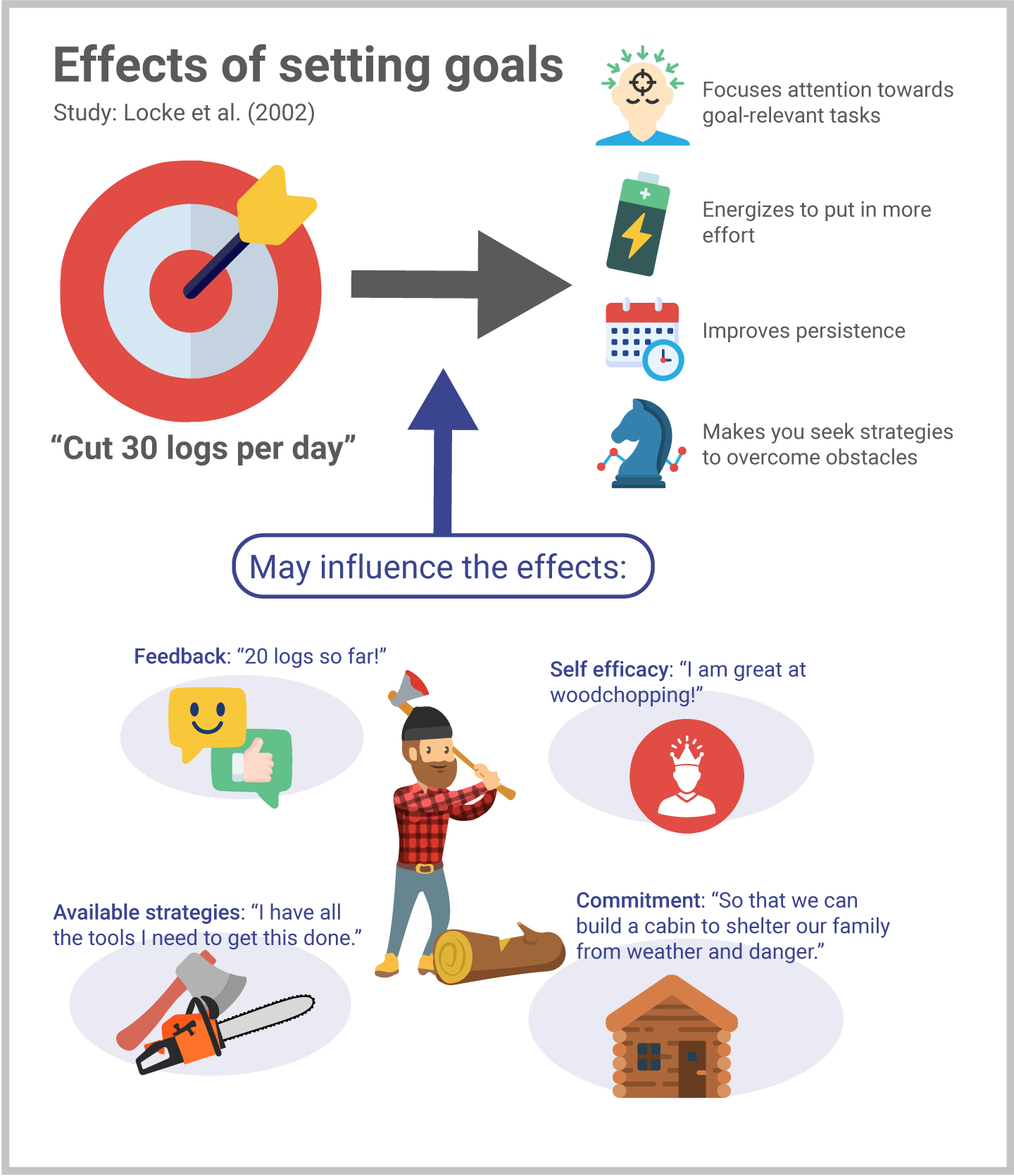

In 2002, Locke and colleagues sifted through 35 years of research and concluded that goal-setting increases performance in 4 ways:

- Focuses attention towards goal-relevant tasks.

- Energizes us to put in more effort.

- Improves persistence in adhering to our desired behavior changes.

- Makes us seek out knowledge and strategies to overcome obstacles to the goal.

The image below summarizes this, including some factors that may influence the effects.

In general, research shows that setting personal goals give us a sense of direction and meaning (Little 1989) and pursuing (and reaching) them makes us happier (Emmons 2003).

- Review SDT book on goal setting evidence

But… There’s a big but: not all types of goals are created equal.

The dark side of the American dream

If extrinsic goals (fame, money, power, beauty, etc.) dominate over intrinsic goals (community building, personal development, improving relationships, etc.), then our wellbeing will probably suffer in the long term (Emmons 2003, Bradshaw 2023). I will expand on that in a later article.

In short: if we value our wellbeing, we should set a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic goals, with more emphasis on the former.

Now back to SMART goals…

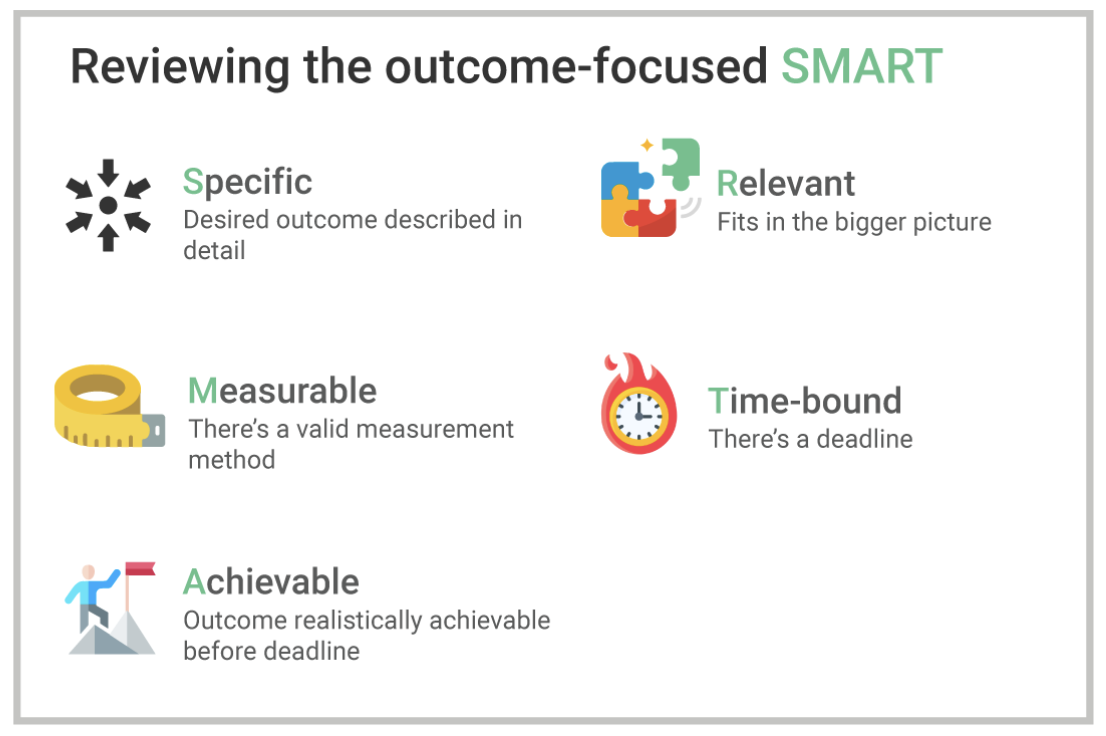

In 1981 George Doran introduced SMART goals so that managers could more effectively get workers to reach certain business targets.

But are SMART goals the right tool for that job? And how effective are SMART goals in other contexts (such as non-work settings)? Should we replace them with an alternative to SMART goals?

Overall, I believe that in many cases, an alternative to SMART goals is more effective: PACT goals.

However, we should not throw SMART goals in the bin completely: they can still be better than PACT in certain situations.

Contents

To support my main thesis, I will first give an example of SMART goals “going wrong”, then show the evidence that SMART goals can be “bad”, then how to understand and apply the alternative: PACT goals, and finally how to decide whether SMART or PACT is best for a certain situation.

More specifically:

- SMART weight loss goals and career goals examples: where it goes wrong

- SMART goals lack “meaning”, making behaviour change harder to maintain

- SMART goals lack intermittent deadlines

- SMART goals focus on the outcome instead of the journey

- SMART goals can destroy self confidence and motivation

- PACT goals: an alternative to SMART goals

- Putting it into practice with the PACT Pyramid

- Choosing between SMART and PACT

- Other article? Making SMART goals smarter

I’ll close off with a conclusion and some practical actions to implement this new knowledge straight away and have more success in achieving goals!

SMART weight loss goals and career goals examples: where it goes wrong

First, I’ll illustrate where SMART goals can go wrong by walking through the goal examples of (1) losing weight and (2) attaining a certain career role.

In both goals, the journey toward the outcome is not very predictable. This is the root cause of the problem, which will become clear when we reach the “Achievable” and “Time-bound” elements of SMART.

Definition of a goal

“Something that you hope to achieve” – Oxford English dictionary

“A purpose, or something that you want to achieve” – Cambridge dictionary

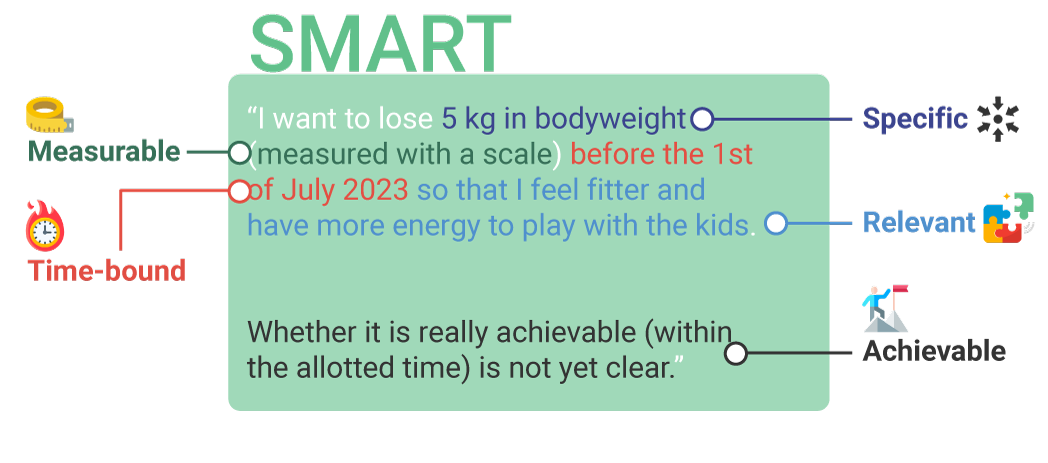

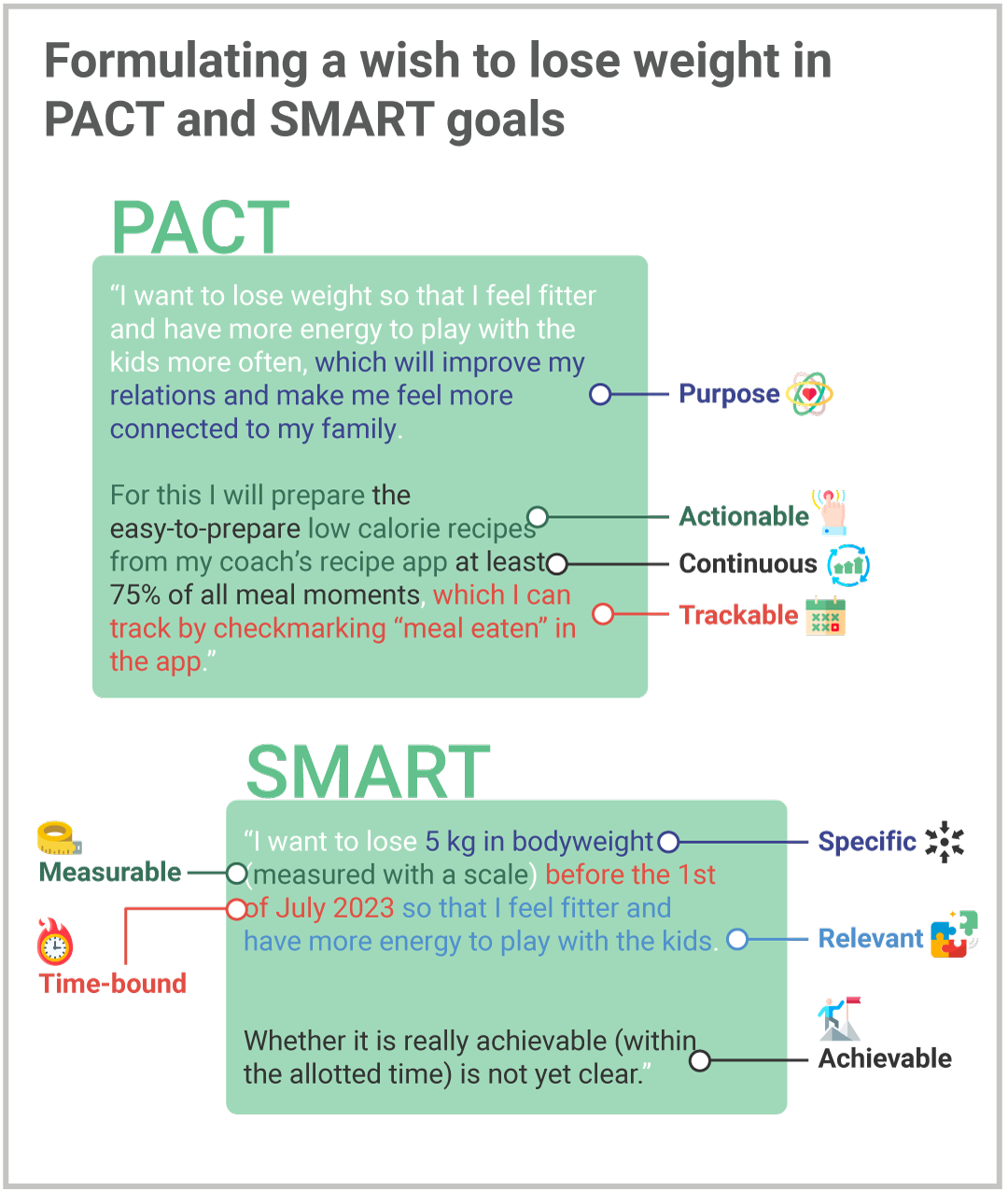

Let’s go through the acronym letter by letter to turn a Wish into a SMART goal:

Specific

Is it clear what reaching the goal would look like?

“I will try my best to lose weight” isn’t good enough.

For a weight loss SMART goal this step is relatively straightforward: we simply state the specific amount of kg’s we want to lose.

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose 5 kg in bodyweight”

Also consider the career goal example.

Goal phrase:

“I want to become a director of sales of a scale-up company with at least 20 employees.”

Measurable

Can we measure our progress towards the goal?

With a weight loss goal, a (bodyweight) scale will do.

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose 5 kg in bodyweight, which I will measure with a scale.”

For the career goal this step is awkward: how can I measure this progress towards the goal?

Are there reliable signals that tell me a promotion or a new job offer are getting closer and closer?

I made an effort, but I am not sure how valid this measure is. It’s like trying to use a ruler to measure a caterpillar’s progress towards becoming a butterfly.

[image trying to measure caterpillar]

Goal phrase:

“I want to become a director of sales of a scale-up company with at least 20 employees, which I will measure through the number of months I outperform my peers in a similar sales representative position.”

Achievable

Do we know whether this goal is actually achievable with our resources? (This includes our skills and tools, but also time resources to achieve the goal before the deadline, see “Time-bound”.)

Often it’s very hard to say whether a goal is achievable (before the deadline), without taking some initial steps towards our goal.

Sure, a personal trainer could tell us what’s possible on average, but the average may not apply to our personal life circumstances.

Therefore, I recommend writing this step of the SMART goal after 2 weeks of seeing initial progress (Bjerke, 2017). I’ll go deeper into that in another article on “making SMART goals smarter”.

[image timeline first attempting a goal, reviewing the process, and THEN deciding on Achievable and Time-bound]

Anyhow, let’s at least try to incorporate the above in our goal phrases:

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose 5 kg in bodyweight, which I will measure with a scale. Whether it is really achievable (within the allotted time) is not yet clear.”

For the career goal, we may do some research to find out how long it takes – on average – to become a sales director when starting out as a sales representative (or another position).

But good luck finding that information, and better luck generalizing that to our personal work situation that is full of unpredictable twists and turns.

Goal phrase:

“I want to become a director of sales of a scale-up company with at least 20 employees, which I will measure through the amount of months I outperform my peers in a similar sales representative position. The goal is achievable in the allotted time according to the industry average.”

Relevant

Why are we setting this goal in the first place? How does it help the bigger picture?

This is rather vague; the main question is to whom the goal is relevant and in what way. To ourselves? To the manager? The business as a whole? The future of our planet?

To weave this criterion into the phrase, we add “so that” to the Specific part and assume the goal is relevant to the person him/herself:

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose 5 kg in bodyweight (measured with a scale) so that I feel fitter and have more energy to play with the kids. Whether it is really achievable (within the allotted time) is not yet clear.”

The relevance of reaching the goal for the career guy:

Goal phrase:

“I want to become a director of sales of a scale-up company with at least 20 employees so that I will have a sense of development and achievement, and earn more money, which I will measure through the number of months I outperform my peers in a similar sales representative position. The goal is achievable in the allotted time according to the industry average.”

Time-bound

By when does the goal need to be reached?

Again, most (and especially long term) goals have such a dynamic and unpredictable journey that it feels like wet finger work to put a single date on when it can realistically be achieved.

The result? Phrases like “Hmm, two years sounds reasonable.”

[image man with finger in the air]

As I previously noted, we could observe how quick the initial progress is and use this to inform when the deadline should be (Bjerke, 2017).

Still, for many types of goals this prediction is inaccurate, as speed of progress will very probably change over time.

And when we underestimate the amount of time we need to achieve a goal, it may lead to a lot of stress, coffee, and cramming to reach the deadline in time.

[image cramming when close to SMART goal deadline]

And worst of all, we may feel like a failure when falling short of reaching the deadline.

We’ll dive into the experimental evidence of these downsides in the article section “SMART goals lack intermittent deadlines”.

But coming back to our goal phrases: to weave the “Time-bound” criterion into them, we’ll add a “before [x time]” statement in front of the “so that” part:

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose 5 kg in bodyweight (measured with a scale) before the 1st of July 2023 so that I feel fitter and have more energy to play with the kids. Whether it is really achievable (within the allotted time) is not yet clear.”

I wish the career man the best of luck:

Goal phrase:

“I want to become a director of sales of a scale-up company with at least 20 employees before the start of the next quarter so that I will have a sense of development and achievement, and earn more money, which I will measure through the number of months I outperform my peers in a similar sales representative position. The goal is achievable in the allotted time according to the industry average.”

And a graphical summary for the weight loss goal:

To drive the point of this article section home, let’s analyze a SMART goal example from the #1 Google ranked article for the search term “SMART goal examples” by BetterUp:

Source: https://www.betterup.com/blog/smart-goals-examples

[turn into an image]

- The “Specific” part of the goal is not actually that specific. What is the concrete outcome the person wants to achieve? If we do not know this, knowing whether it’s attainable in a month becomes even more impossible (see “Time-bound”).

- What does the way we will try to achieve the goal have to do with whether progress towards the goal is measurable? How will he measure whether the team members feel like they can “more effectively” communicate? Perhaps would a questionnaire help here?

- There is no concrete goal, so it’s hard to decide whether it’s Attainable in the allotted time.

- Time-bound: is there also a baseline measurement of how virtual communication is going? Otherwise, what can he compare the final measurement to?

Recap:

SMART goals were invented to better manage people within a business. Applying the SMART letters in personal, long term goals in dynamic circumstances becomes problematic.

Apart from the ambiguity and difficulty of applying the SMART letters in the examples above, in the following sections I’ll tell you about the (science of the) other problems with SMART goal setting.

Teaser: A lack of motivation, wellbeing and self-confidence are ahead.

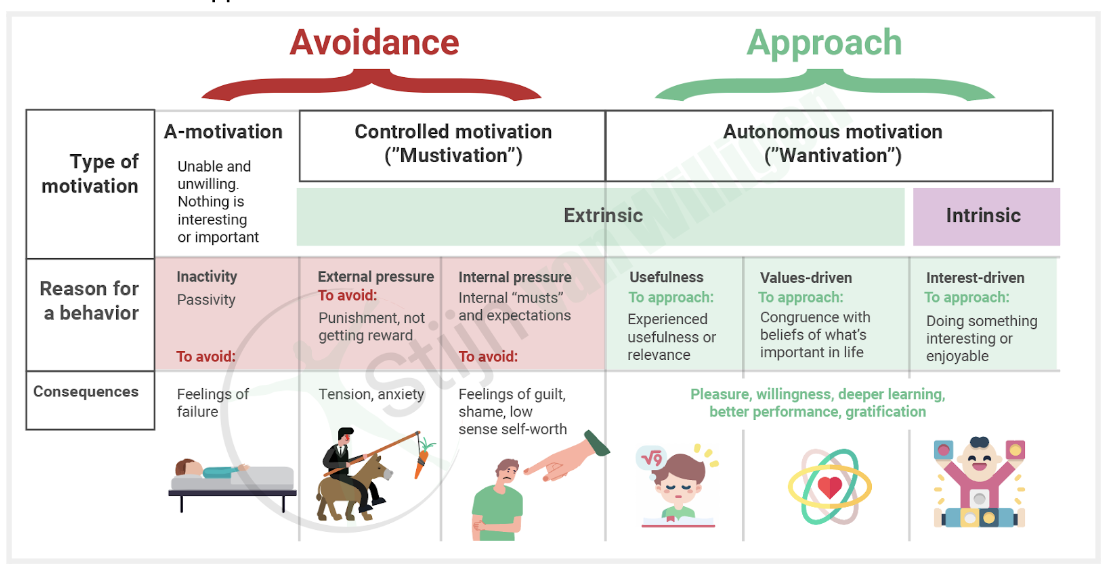

SMART goals do not encourage giving deeper meaning, making behaviour change harder to maintain

The 5 SMART letters all focus on the cognitive aspect of a goal.

This implies that all we need to reach our goal are rational metrics and a deadline, without identifying a deeper personal meaning or purpose.

Giving meaning (asking ourselves “why”) to our goals aligns them more with our personal values and ambitions.

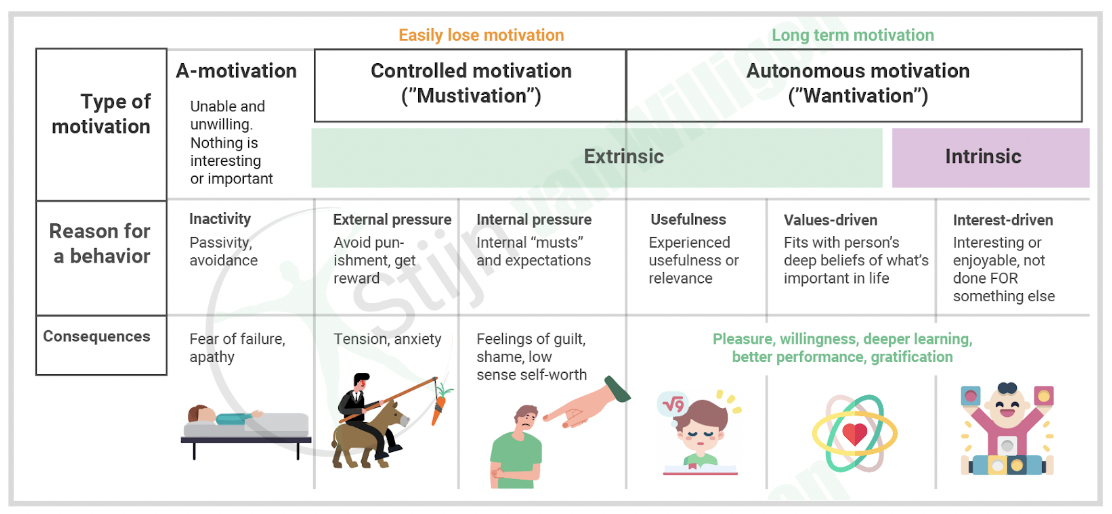

This is crucial for staying motivated in the long term: we perform the new behaviors willingly (autonomous type of motivation: “I want to”), instead of feeling like we should do them (controlled type of motivation: “I have to”) (book Ryan & Deci, 2017 ed.).

The latter type of motivation, I like to call “Mustivation” (credits to Chi Chiu).

[image types of motivation]

Now you may be wondering what evidence I have to back up that claim.

An analysis of 184 individual data sets shows “wantivation” is related to implementing healthy behaviors in the long term (Ng, 2012), and another analysis of 66 studies shows it’s related to maintaining exercise and physical activity in the long term (Teixeira 2012).

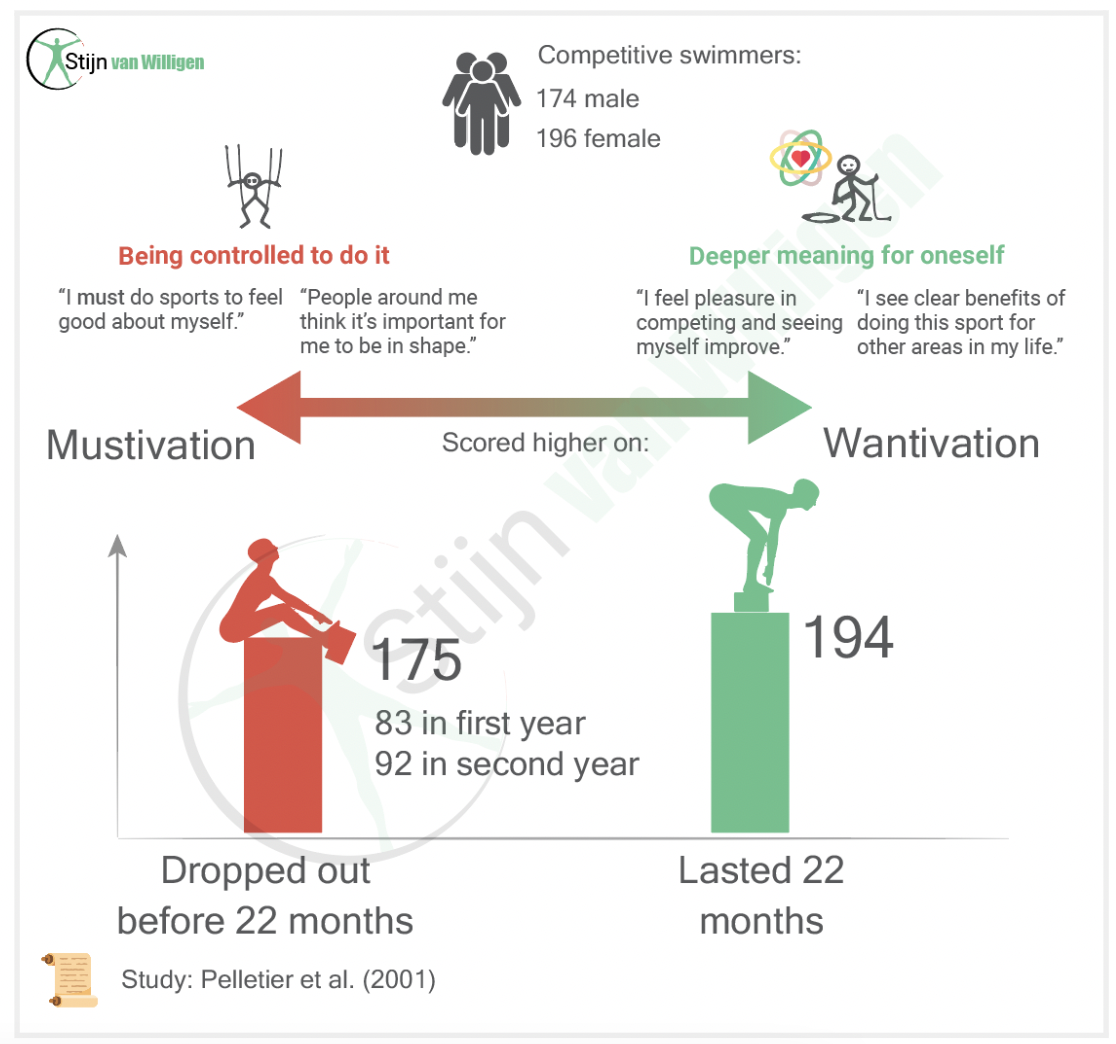

This specific study (Pelletier 2001) in swimmers illustrates how powerfully giving meaning to our goals relates to sustaining highly demanding behaviors (to achieve the goal).

With questionnaires, they found out whether the swimmers had a deeper meaning behind their swimming practice, or were mostly controlled to do the work by outside forces.

Then they looked at how long they sustained the high effort practice…

Two well-designed experiments in the context of weight loss (Williams 1996) and exercise (Silva 2010) programs further support how important giving meaning is.

Still, for shorter term goals, more controlled types of motivation can do the trick.

For example, a pressing deadline to pay a bill to prevent a penalty will often get us into action. In such situations the outcome-focused and “not personally meaningful” SMART goals are more appropriate.

Recap:

SMART goals don’t let us reflect on the deeper meaning of achieving the goal. This undermines autonomous (self-willing) motivation, also called “wantivation”, which science shows is important to sustain new behaviors.

SMART goals lack intermittent deadlines

We humans are very bad at what SMART advises: setting a single deadline. Left to our own devices, we either set them too early, or too far.

Setting them too early results in a huge wake up call: “Ah, I thought I could lose those 10 pounds in 2 weeks!”

But mostly, we set single deadlines too far into the future, simply because we don’t really know how long it would take to reach the goal.

But this wastes a lot of time. Why?

Procrastination.

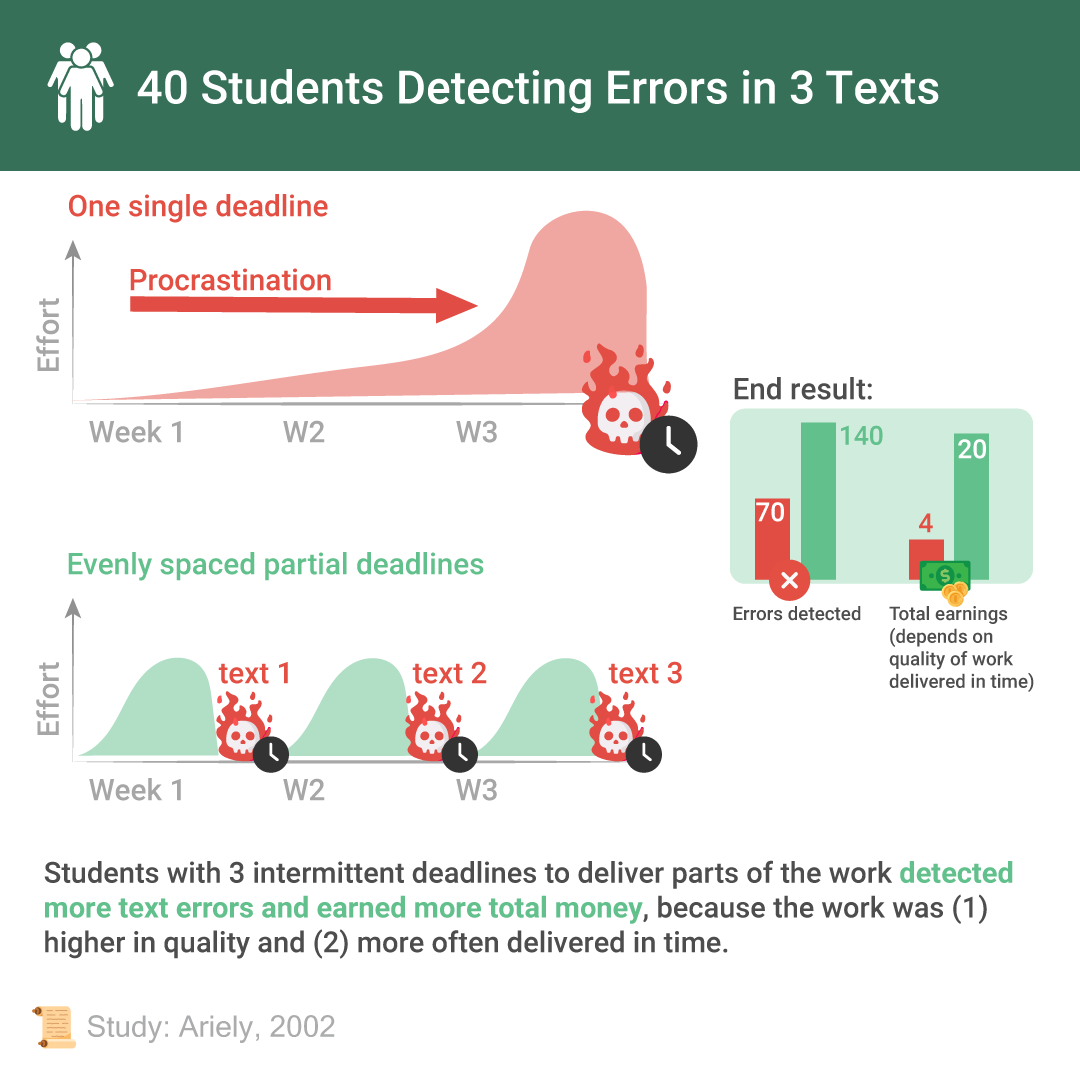

In general, we humans postpone taking action until the very last minute, unless intermittent deadlines are “forced” on us (Perrin 2011, Johnson 2016).

For example, I often find myself doing some cleaning around the house instead of doing the most important things to make progress on my goals, like sitting down to write this article.

Procrastination makes sense: there is no day-to-day or week-to-week urgency.

However there are clear downsides: we tend to stress like crazy in the last days leading up to the single deadline and are more likely to make mistakes. Not-so-nice.

Researchers believe this last-minute “scarcity of time” to finish the work gives us more focus, or “tunneling”, on the activities of that work (Piech 2010, Kurtz 2008).

[Image focus increasing when getting closer to a deadline and distractions bumping off against shield, but also missing some crucial details]

We can notice this ourselves too: distractions like phoning up a friend or watching an extra Netflix episode are easier to resist during those last hours before a deadline.

And although the increased focus makes us miss distractions, it also makes us more likely to miss important details of the work itself, which leads to lower quality of work.

So if we have a SMART goal (1 big deadline) to give a presentation to our colleagues on a certain date, the slides will likely contain some mistakes.

And this is even true for something like a weight loss goal: a single deadline, more disappointing results (Freund, 2011).

An experiment by Ariely and colleagues (2002) beautifully illustrates all the above, and advocates for setting more than 1 deadline.

40 students needed to correct errors in 3 texts for money compensation. Half of the students had one single deadline before which to deliver the work, and the other half had multiple evenly spaced deadlines for each one of the 3 texts.

See the results:

[image burst of effort at the end, or graph of performance under evenly-spaced deadlines]

As an additional benefit: every deadline we successfully hit gives us a sense of achievement, which motivates us to keep up the good work to reach the next milestone (Ariely 2002, Höpfner 2021).

Recap:

We humans are bad at setting a single deadline (which SMART recommends) and often put the deadline further in the future than needed. Also, this long-in-the-future deadline leads to procrastination. Rather, I recommend creating multiple intermediate deadlines (milestones), which is shown to lessen last minute stress and to make us produce better work with a higher sense of accomplishment.

SMART goals focus on the outcome instead of the journey

Related to having a single deadline, SMART goals are focused on a single outcome. This creates multiple problems:

- The SMART goal doesn’t clarify what we need to do from day to day, week to week to reach the desired outcome, which is essential to reaching your goals (Gollwitzer 2006).

- The outcome of the goal reigns supreme over “The way to get there”. However, focusing on the process of achieving the goal instead of the outcome is linked to feeling happier (Kaftan, 2018), but also increases our chances of actually reaching the finish line (Freund, 2011).

The latter makes sense to me: focusing on the gigantic end goal of finishing this article leaves me paralyzed, but focusing on writing 2 hours today makes me feel like I am making progress. And this “sense of success” is thought to be very important (Ariely 2002, Höpfner 2021).

[image highlighting study-proven benefits of process focus instead of outcome, and the mechanism of Feeling competent when you finish a small step at a time]

A related tip: Every night or every next morning, we should reflect on the progress we have made on our goals. What did I do today that moved the needle forward? It’s bound to leave us more satisfied and happier about our days.

Recap:

SMART goals focus on outcome, which is linked to less likelihood of achieving the outcome, but also to less wellbeing than when we focus on the process.

But there’s more: very ambitious SMART goals may seriously negatively affect our mental health.

SMART goals can destroy self confidence and motivation

Research shows that setting an ambitious and specific goal (such as with SMART) and then failing to achieve it likely reduces our emotional state, self-confidence, and motivation for pursuing such goals in the future (Höpfner 2021).

[image showing experimental results]

This is in line with the highly proven Self-Determination Theory: if our perceived competence decreases (because we did not achieve a goal), our motivation will decrease (Ryan & Deci 2017).

Read more about the Self-determination theory and the motivation continuum in my other blog post.

As we can imagine: this is especially a problem in the workplace.

When managers keep setting outcome-focused SMART goals, and employees do not achieve them, in the long term they will become less and less motivated.

They will likely choose easier tasks and avoid challenges to protect their self confidence from sinking even further by failing to reach additional overly ambitious goals.

So in the long term, businesses may cultivate a less confident and less effective workforce due to high and specific SMART goals.

Luckily, we can do things to counteract the negative effects, and even make ourselves and employees strive for better performance than what was expected, which I’ll discuss in my separate article “making SMART goals smarter”.

Recap:

Setting an ambitious and specific goal (such as with SMART) and then failing to achieve it can reduce our emotional state, self esteem, and motivation for pursuing such goals in the future.

PACT goals: an alternative to SMART goals

Now we arrive at an alternative to SMART goal setting, which tackles most, if not all, of the previous downsides of SMART goal setting: PACT.

[Pim: image showing PACT and crosses through the different previous negative effects of SMART goals sections]

The biggest difference?

PACT focuses on behaviors that we can predictably control day in, day out (focus on the continuous journey itself), while SMART focuses on the (unpredictable) long term outcome (what we hope to get after the journey).

It is unknown who first came up with PACT goals.

As with SMART, the letters of PACT tell us what the formulated goal should adhere to.

Let’s first review what SMART stands for, and then go through the PACT letters one by one.

[image arrows evidence giving meaning]

Purpose

What is the goal, and what meaning does achieving that goal have in the person’s life?

Remember how important describing the meaning of a goal is to sustaining motivation in the long run? The first letter makes this happen:

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose weight so that I feel fitter and have more energy to play with the kids more often, which will improve my relations and make me feel more connected to my family.”

The portion in bold is an expression of the person’s values relating to Benevolence (friendships and relationships) and Family Security.

And it doesn’t end there: we can also apply PACT to a work-related (personal) goal. Let’s give it a try:

Goal phrase:

“I want to perform in a role with more responsibilities in my work domain so that I will get challenged more and earn more money, which will challenge and improve my decision-making for work-life balance and capacity to donate to charities for less hunger in the world.”

The portion in bold is an expression of the person’s values relating to Wisdom (life judgment) and Equality.

[image arrows evidence deadlines and implementation intentions]

Actionable

Is the goal active and does it describe concrete steps that have to be taken (day in and day out)?

This integrates some of the power of intermittent deadlines and Implementation intentions into the goal formulation.

Intermittent deadlines

It is much easier to determine what actions are achievable for shorter stretches of time, like per day or per week.

Implementation intentions

Implementation intentions are simply “IF [trigger of behaviour] happens THEN I will do [new behaviour]” statements, and formulating them is super effective to maintain behaviour change and reach your goals, because it removes the vagueness around what needs to get done (Vilà 2017, Gollwitzer 2006).

[Image: estimating optimal time for multiple steps vs. estimating a grand deadline where smaller steps are not defined. Person preparing meals every day. Use stepping stones over a river as a metaphor.]

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose weight so that I feel fitter and have more energy to play with the kids more often, which will improve my relations and make me feel more connected to my family. Every day I will prepare low calorie recipes from my coach’s recipe app.”

For attaining a certain job position:

Goal phrase:

“I want to perform in a role with more responsibilities in my work domain so that I will get challenged more and earn more money, which will challenge and improve my decision-making for work-life balance and capacity to donate to charities for less hunger in the world.

Every morning for 1 hour I will follow, summarize, and quiz myself with an online education in a skill I need to improve most.”

[image arrows process-focused]

Continuous

Is the goal aimed at continuous improvement, instead of a static end result?

Because there is not a single static outcome we have to reach before a certain deadline, PACT allows for a more flexible approach.

Of course, we may have off-days where we cannot read for 1 hour, but perhaps we can still read 15 minutes that day.

The progress towards the goal slows down, but there is still continuous improvement.

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose weight so that I feel fitter and have more energy to play with the kids more often, which will improve my relations and make me feel more connected to my family. Every day I will prepare the easy-to-prepare low calorie recipes from my coach’s recipe app at least 75% of all meal moments, on as many days as possible.”

The “at least 75%, on as many days as possible” indicates that we’re trying to get better over time (continuous improvement), but missing (to plan) a meal here and there is not the end of the world. In other words, it will not trigger a “screw it, now that I missed my breakfast I might as well feast on 5 pizzas” reaction (Polivy 2010).

[image of weekmeals.co app week planning of meals ]

[mother who has ups and downs and reaches goal VS. mother that has a great streak and then crashes in the weekend: compensates for all calories of the week]

Similarly, not being able to study for 1 hour on an unexpectedly busy day should not trigger a “then I will not read at all today” reaction.

Applied to the job position PACT goal:

Goal phrase:

“I want to perform in a role with more responsibilities in my work domain so that I will get challenged more and earn more money, which will challenge and improve my decision-making for work-life balance and capacity to donate to charities for less hunger in the world.

Every morning for 30 min to 1 hour I will either follow, summarize, or quiz myself with an online education on a skill I need to improve most.”

[evidence of progress as feedback to goal, Trackable]

Trackable

Can the progress towards the goal be tracked consistently?

It’s important we get feedback when we’re pursuing a goal (Locke 2002). If we don’t know how we’re doing, how do we know whether to adjust our strategy?

For example, if our goal is to cut 30 trees per day, there has to be some way to know how many we’ve already cut. Then we can adjust our effort, or change the strategy entirely.

Goal phrase:

“I want to lose weight so that I feel fitter and have more energy to play with the kids more often, which will improve my relations and make me feel more connected to my family. Every day I will prepare the easy-to-prepare low calorie recipes from my coach’s recipe app at least 75% of all meal moments, which I can track by checkmarking the “meal eaten” option in the app.”

Now let’s observe the SMART and PACT version of the goals side by side:

[image side by side comparison]

Recap:

An alternative to the SMART goal is the PACT goal, which focuses on the process instead of the outcome. Formulate these goals by ensuring they are Purposeful, Actionable, Continuous, and Trackable.

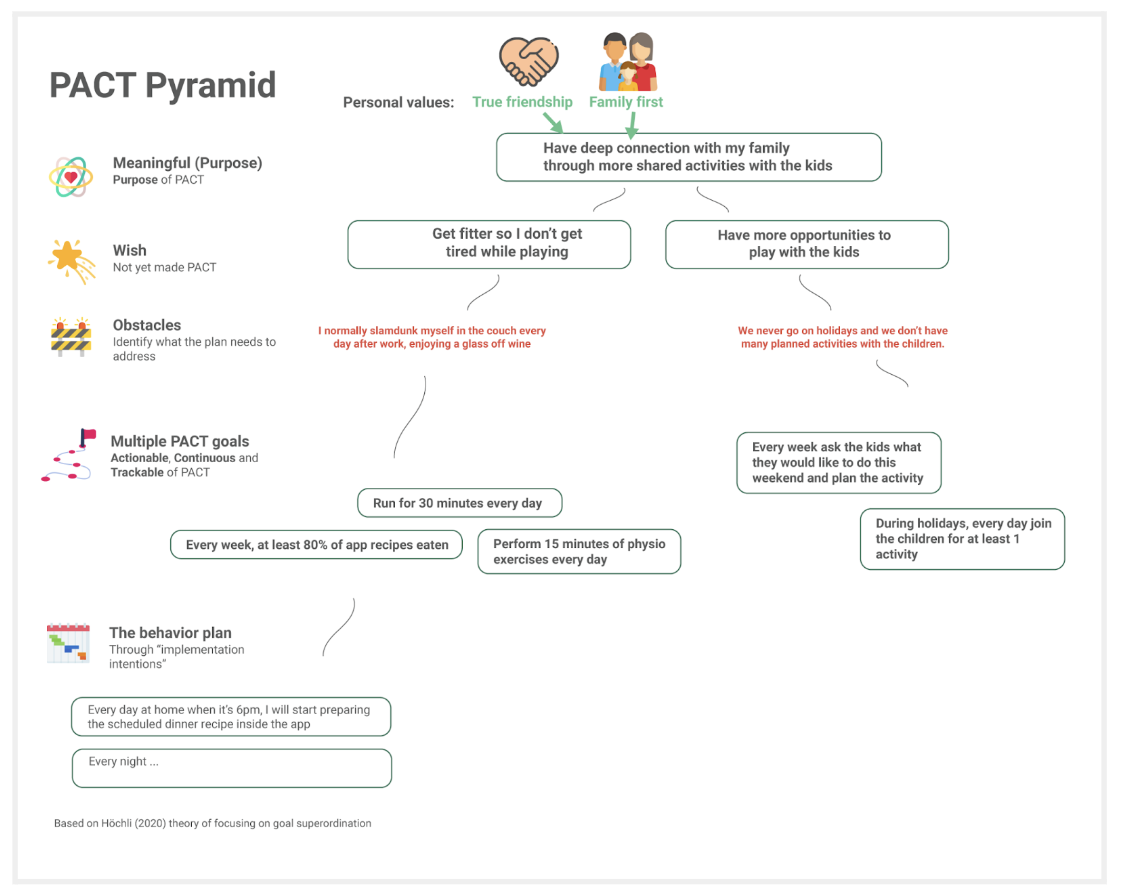

Putting it into practice with the PACT Pyramid

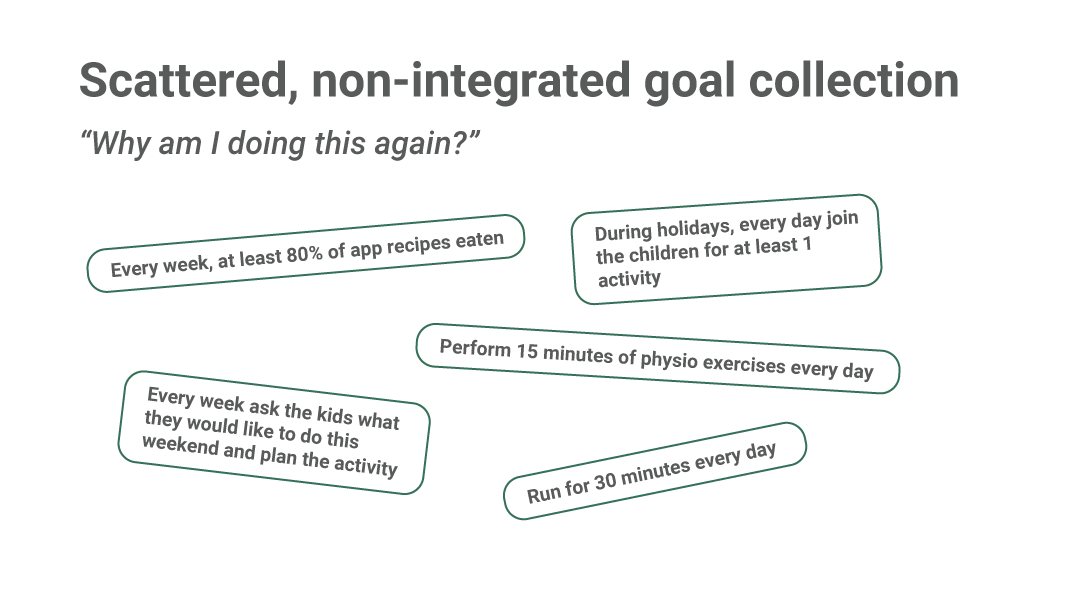

Often we don’t want to set a single PACT goal, but multiple, because there are multiple things that contribute to the higher purpose we want to achieve in our lives.

But in a scattered forest of goals, over time we may forget what we’re doing this all for: the emotional value of the scattered goals decreases.

Therefore I present the PACT Pyramid: a way to integrate multiple PACT goals into a framework based on the concept of “Goal superordination” by Höchli et al. (2018).

“Goal superordination” basically reminds us how all our goals and related day-to-day actions tie together into a “higher meaning” (Purpose) that represents our personal values.

It reminds us that not everything needs to be fun, but needs to be important enough to “suffer” voluntarily for, such as (for most normal people) running for 1 hour every weekend.

It motivates us in the long term by giving meaning (Ng, 2012).

Let’s look at the schematic overview and then go through the pyramid levels one by one:

Level 1: Purpose

As we can see from the image, our personal values dictate the Purpose of PACT, at the top of the pyramid.

Note that if we value extrinsic things (and therefore pursue mostly extrinsic goals), we are more likely to become unhappy by achieving those goals, because it often frustrates our basic psychological needs (book chapter 11, Ryan & Deci 2017).

[Find powerpoint slide (day 4 veranderkunde) values circle and goals, to copy, and instill Schwarz separate values on the circle]

More insight into our personal values?

Perform this personal values test, based on the highly scientifically validated Schwarz theory of personal values (source).

Level 2: Wishes

We can see a Wish as what a person answers us when we ask “what do you want”. Wishes often aren’t specific enough to be PACT goals, but concrete enough that you can line them up with a personal value of that person.

I am, as you have guessed by now, a big believer in living in line with your personal values (and therefore striving for goals in line with personal values).

The Wishes should be approach oriented and not avoidance oriented for higher odds of success (Oscarsson 2020, Church 2001) and subjective wellbeing (Elliot 1997).

We can roughly categorize the Mustivation and Wantivation types of motivation into both Avoidance- and Approach-oriented Wishes:

Studies show potential mechanisms for more subjective wellbeing with Approach-oriented Wishes:

- We perceive more progress happening (Elliot 1997);

- We are more autonomously motivated when we do things to achieve something (that we find valuable) instead of doing things to avoid negative evaluations, judgments, or feelings (such as shame or guilt) (Church 2001), and this is indeed in line with the Self-determination Theory motivation continuum (source).

See the image for more specifics.

[image approach vs avoidance goals and the thought mechanism by Elliot]

Examples of Approach oriented Wishes are:

- “Get promoted to a higher position within my company within the next year so that I get challenged more.”

- “Create a free, successful graphic design YouTube channel so that I can offer education to anyone in the world, rich or poor.”

- “Complete a series of paintings and have an art exhibition to showcase my work so that I can create new connections with like-minded people.”

Examples of Avoidance oriented Wishes are:

- “Quit smoking so that I can avoid the health risks associated with tobacco use.”

- “To complete assignments well in advance so that I can avoid last-minute stress and potential late penalties.”

However, when we ask ourselves the right questions, we can find more autonomous forms of motivation for our Wishes and easily make them approach-oriented. For example:

- “I want to have more smoke-free days so that I feel fitter…

- … and give a great example to my children (value: Family).”

- “I want to finish assignments early so that I am more relaxed …

- … and can be more present in my interactions with loved ones (value: True friendship) and play my guitar with an empty mind (more space for fun activities).”

[image transformation arrow and question “formulate this wish in a positive way, and what it could add to your life”, flipping a “downward step to hell” to “a mountaintop to reach”]

Level 3: Obstacles

Obstacles are the things we perceive to stand in the way of accomplishing our Wishes. You can uncover them by asking yourself: “What have I tried before to reach the Wish, and what stopped me from reaching it during that try?”

Often, they are perceived obstacles, such as limiting beliefs…

[image with people (on the mountain if possible) with talking bubble:

- “I can’t create YouTube videos because I am not good enough on camera.”

- “I can’t give a lecture because I do not have enough expertise. And people will think I’m full of myself””

- “I can’t post my art on social media because my friends and family will make fun of me”]

Level 4: PACT goals

The Wish and Obstacles convert the Purpose into our separate PACT goals, because they teach us our direction (Wish) and what behaviors we should focus on to overcome the Obstacles in our way when we take that direction.

We already discussed at length what a PACT goal could look like. The new information is that we should tailor the PACT goal to the Obstacle standing the most in the way of reaching your Wish.

[image Obstacle standing in way of the Wish – the strategy to overcome the obstacle]

For example, when you have a false, limited belief that you’re not good enough on camera to start a YouTube channel, you should focus your PACT goal on overcoming that obstacle.

Concretely, your PACT goal could be to practice with your video script every day and to get feedback from an experienced video creator every week.

This will likely increase your sense of competence over time, and thereby your confidence in yourself (Wouters 2014, Deci 2001).

[image link of enhanced basic needs related to True self-confidence Wouters 2014]

Level 5: The behavior plan

Finally, the behavior plan spells out what we’re going to do on a day-to-day basis to make continuous progress on the goals, and where/when we perform these actions.

We call these actions in our action plan “implementation intentions” (IIs).

As I explained in the “Actionable” part of the PACT section, implementation intentions describe when and where we will do what.

[image sun comes up on mountain, time to get your script, set a timer, and practice]

For example: “When in the morning my alarm goes off, then I will go into my home office to meditate for 10 minutes.”

A compilation of almost 100 scientific experiments shows that setting implementation intentions is very effective for goal achievement (Gollwitzer, 2006).

Researchers believe it’s because they are very concrete actions that ultimately lead to people automatically showing a certain behavior (the what) after a certain trigger (when/where): habit formation.

Habits are behaviours we perform unconsciously that require almost no willpower, and involve no thinking or emotion (Vilà, 2017).

Therefore, we can sustain habits in the long run.

[image car driving habits]

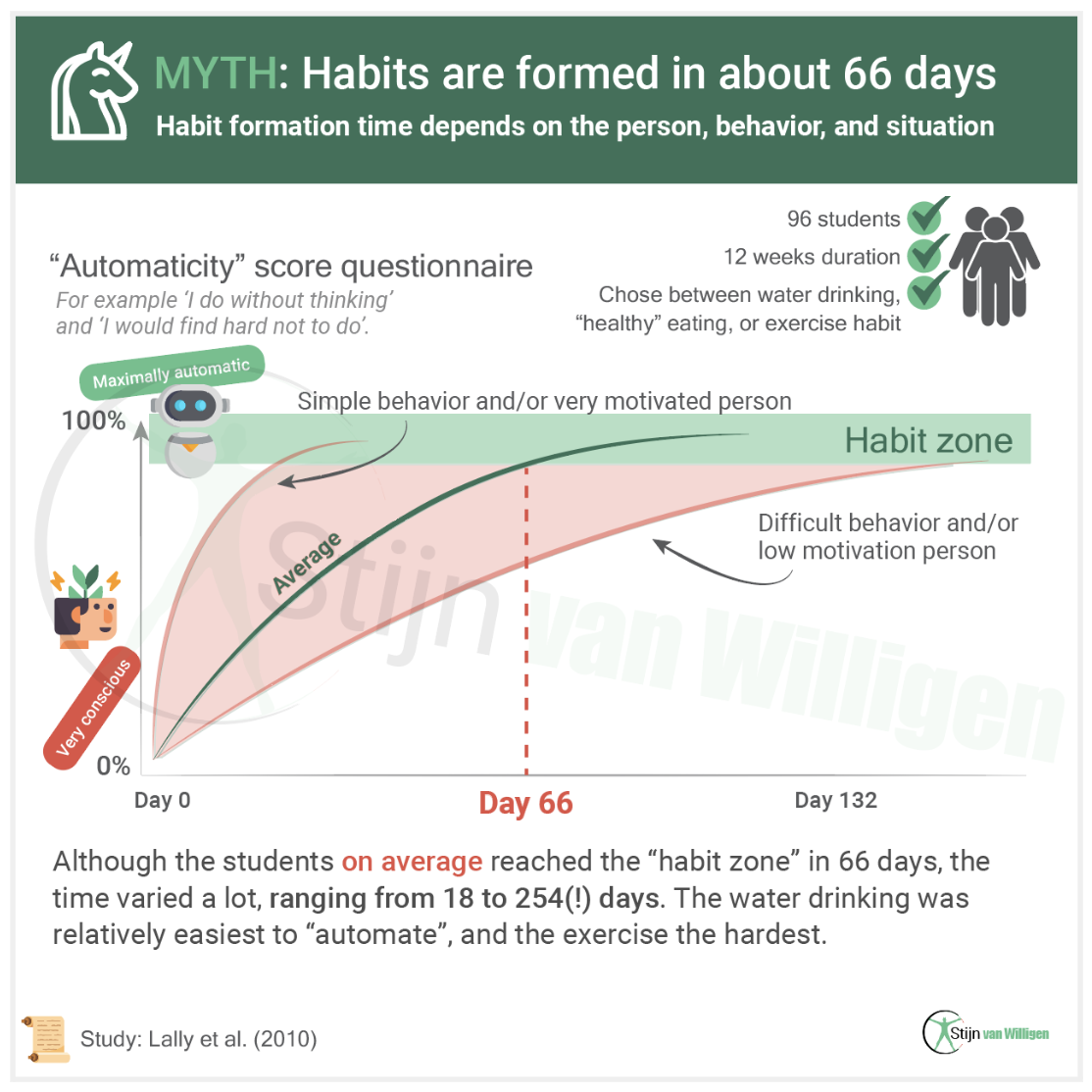

There’s a myth (example publication) that it takes about 21 days to form a new habit, based on … A study by Lally (2009) points us to an average time-to-habit of 66 days.

However, an average is an average: it does not say anything about the variation in the “time to habit formation”, which was as follows:

[image 66 day habit formation]

60 second video variant

So is our habit formation comparable to the data point on the left, or on the far right? It really depends on many things, most of all how difficult it is for the person to automate the new behavior.

Note also that these needed actions (and habits) towards the goal may continuously change based on (life) feedback.

Continuously checking whether we’re still going (daily actions / habits) in the right direction (deeper meaning) is essential.

Bonus: this automatically keeps our main Purpose for doing certain things fresh and clear in our minds, which can push us through the difficult moments.

[image feedback loop daily actions, outcomes, and how they relates to deeper meaning – diary “check pact pyramid”]

Recap:

We can use the PACT Pyramid to create overview in our goals and remind ourselves of what we’re doing it all for. The pyramid’s levels are: Purpose > Wishes > Obstacles > PACT goals > Behavior plan.

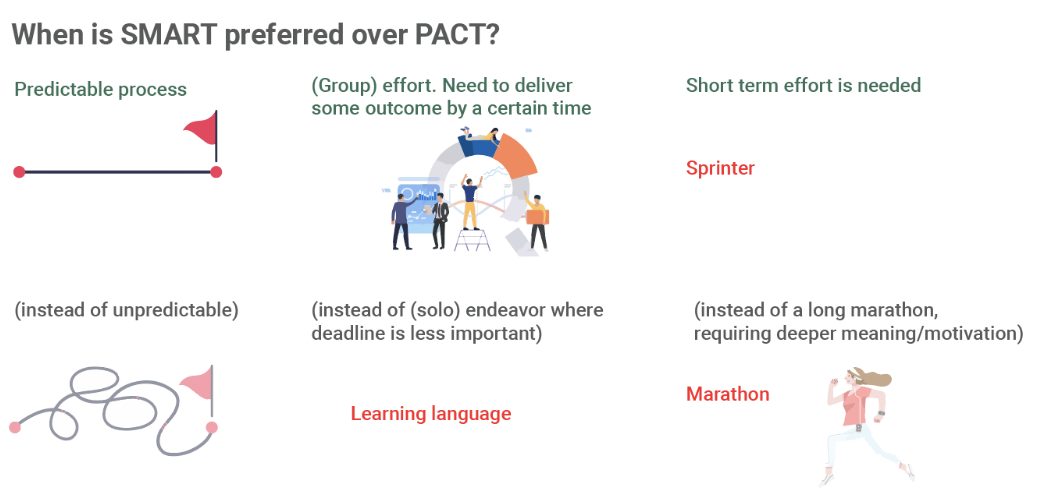

Choosing between SMART and PACT

There are definitely situations where I recommend SMART goals over PACT goals, especially when the process towards the goal is predictable (such as saving up x money before y date) and not a long, dynamic journey which requires sustained effort, or when a team of people work together towards a certain output by a certain date (such as a business project).

But again: beware of how it affects employees’ self confidence and motivation when they repeatedly miss (challenging and specific) SMART goals.

[image choice between end goal with a predictable process (train tracks) and end goal hidden behind a jungle with many changing variables]

However, when we’re trying to change behaviours or habit patterns to achieve a long term personal goal, I recommend going with multiple PACT goals (inside a PACT Pyramid) that focus on the journey.

Now let’s pull this all together in the way I love: with a schematic image.

It highlights the main differences between SMART and PACT goals, including specific examples of both.

[image differences between goal setting, including formulation with color coding]

Recap:

When the journey towards the goal is long and unpredictable, and reaching it has deep personal meaning, then I recommend setting a PACT goal. E.g. “Become a better friend”, “Become a better cook”, “Get fitter”.

When the goal is short term and/or involves ourselves or our team working towards a certain outcome that has to be delivered by a certain date, choose a SMART goal. E.g. “Deliver market research report”, “Fit wedding dress before wedding date”, “Deliver new website”.

Conclusion

SMART goals are often chosen in the wrong situations, and guidelines on the internet on how to formulate the goals often lead to confusion and ineffectively phrased goals.

When our goal is for the long term, has deep personal meaning, and the journey towards it is unpredictable, we should formulate them as PACT goals, because it increases the odds of succeeding and being happy on the journey.

This was truly valuable and so well explained. Thank you very much!! Wonderful article and very helpful and practical.

Thank you Susan, that’s wonderful to read.